HOME

Contact

Links

Sources

LogbookAIRCREW

Troup

Naylor

Herrick

Hewson

TACTICS

Training

Blenheim

Weapons

Formations

Tasks

MISSIONS

Scharnhorst

St Nazaire

Brest

Schiff 24

UJ 126

Condorcet

|

|

Kriegsmarine 'Shiff 24'

- Formerly Fishing Vessel 'Mars' or 'Saturn?'

Schiff 24 - The Ship With No Name

'Ship 24' . The ship with no name

- and yet several names. An armed decoy trawler that

masqueraded under many disguises, and many national

flags, following a historic tradition of naval deception

dating back hundreds of years. Perhaps the concept is

best known today as a 'Q' ship, such as the large

disguised merchantmen that were utilised to great effect

by the German Navy in the First World War.

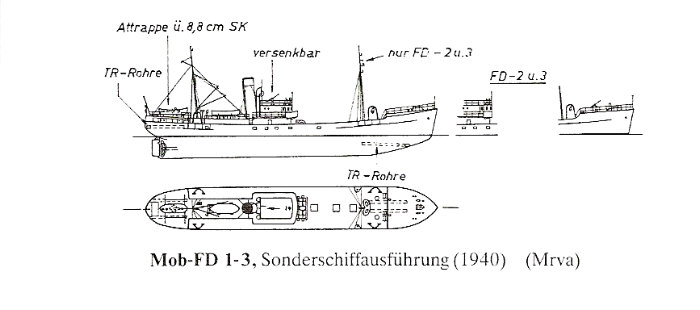

But Schiff 24 belonged to a smaller class

of vessel, one whose role was to blend in with the local

fishing fleets and monitor coastal activity along the Bay

of Biscay. Operating alongside its sister ship, 'Schiff

13', it reported on the movements of ships and aircraft

in its area of operation, whilst also acting as a trap

for enemy submarines ('U-Bootfalle').

French, Portugese, and Spanish disguises

were carried, amongst others, to conceal not only its

identity but also the 8.8cm quick firing canon hidden

under a dummy lifeboat and the retractable 30cm machine

guns under concealed trapdoors, as well as the torpedo

tubes and anti-submarine equipment. In age-old naval

tradition, it was not illegal to sail under false colours

as a ruse - but in order to open fire or fight, a ship

was expected to display true identity (hence the 'raising

of the flag' scene, so common in wartime naval movies').

Although some evidence is contradictory,

it would appear that on 22 June 1941, Schif 24 was to

become the target of two Blenheim aircraft from 53 Sqn

based at RAF St Eval, in an encounter that left both

sides nursing their losses. The story today begins with

the brief entries in Charles' logbook: "Strike

on enemy M/V, 1000 tons, 4x250 G.P. 1 glanced off decks.

P/O Williams (A/C Y) turned before ETA. P/O Hewson (A/C

F) missing after leaving scene of attack."

Eric 'Nine-Lives' Hewson was a

close friend of Charles', who had initially trained with

him but had slipped back during the courses due to a

sequence of aircraft accidents that had earned him his

nickname. He had only recently joined 53 Squadron and

this was one of his first few operational sorties. The

day was to confirm his nickname in the most dramatic of

circumstances.

Another new squadron member P/O

Williams may have 'turned before ETA' for this

particular attack (did that annoy Charles? It is recorded

in other reports that Williams 'broke formation') but

records show that after turning away at 2051hrs Williams'

aircraft then dropped its bombs at 2128hrs in a more

northerly position on an ocean-going tramp steamer of

about 1500 tons in a convoy of 11 ships. Indeed, that

convoy would seem to have been the original target for

the mission; the tasking order asked for '6 aircraft of

53 Sqn and 1 of 217 Sqn to attack 14 motor vessels

reported at 1500 hrs. (AIR 25 459)

Tactics in Coastal Command had

changed since the high-level bombing attacks on the

Battle Cruisers and Naval Facilities during April: it had

been realised that the chances of hitting a ship from

high altitude were small. Consequently, low level

shipping sweeps over the Bay of Biscay were introduced,

with the aim of finding and destroying coastal shipping

on routes from Spain to the West Coast of France or

U-boats setting out on or returning from patrol in the

Atlantic. The advantage of this tactic was a hugely

increased chance of a bomb hitting the target as the

aircraft ran in directly towards it in a single vertical

plain: the disadvantage (for the same reason) was that of

becoming a straightforward target for anti-aircraft fire,

with little scope for evasive manoeuvering. PRO AIR

15/247 (Bombing Attacks by CC Aircraft on Enemy Surface

Craft - Record and Analysis) shows how the bomb hit rate

compared to height of release was analysed at the time,

in order to confirm the tactic. It would appear that only

attacks from less than 200' were ever succesful. Forty

years later, during the Falklands Conflict, the same

effect could be seen as Argentinian Skyhawks bravely and

succesfully used similar tactics with essentially similar

bombing equipment against Task Force shipping in

Falklands Sound. AIR 15/298 from July 1941 consolidates

the Coastal Command policy with instructions to attack

from the beam if the vessel is unarmed and from directly

ahead or astern if armed (in order to reduce the number

of defensive guns that could be brought to bear). The

aiming point for a beam attack should be the side of the

ship, and for an end-on attack the deck. It notes that

10% of hits would be 'glancing' and also helpfully

advises that the aircraft's forward guns should be used

to suppress flak during the attack.

The Coastal Command Narrative for

22 June 1941 (PRO AIR 24/379) adds detail to Charles'

logbook entry: "Aircraft B of 53 Squadron

dropped 4 x 250 lb General Purpose bombs on 1 motor

vessel at 2118 hrs from 50'. One bomb fell on deck and

bounced off without exploding. Two bombs overshot.

Fragments presumeably from a bomb hit aircraft which felt

explosion about 2 seconds after aircraft passed over

ship. Aircraft F is overdue from strike."

The 53 Sqn F540 records slightly more detail: "Direct

Hit on target observed but bomb failed to explode.

Fragments, presumeably from a bomb, hit aircraft in wing,

tailplane, and engine."

'Fragmentation damage' is a common

problem with low-level bombing attacks: after release a

slick bomb will continue to travel at much the same speed

as the releasing aircraft and will hit the target the

same time as the aircraft overflies it. In order to

prevent damage from one's own bomb fragments, a time

delay was set into the bomb fuse (often 11 seconds for CC

aircraft) so that the aircraft would be clear of the area

- but such fuses were not always reliable. An alternative

solution which was more common post war was to 'retard'

the bomb using plates which deployed into the airflow

after release, so that the bomb travelled more slowly

than the aircraft.

No further details of circumstance

leading up tothe attack could be found in the British

records, so to complete the story it now needed an

examination of Schiff 24's Kriegstagebuch (War Diary).

Fortunately, this had survived along with the majority of

German Naval records which were captured towards the end

of the war, and a desciption of the attack is here given

in the words of the ships's Captain Bludau (in my best,

but very poor, effort to translate from the German, for

which I apologise):

Bridge of “Schiff 24”

Lorient, 24 June 1941

To:

Western Naval Command Paris

Western Defence HQ Paris

3rd Coastal Defence Division Brest

Re: Combat Report on the bombing attack which happened on

the 22 June.

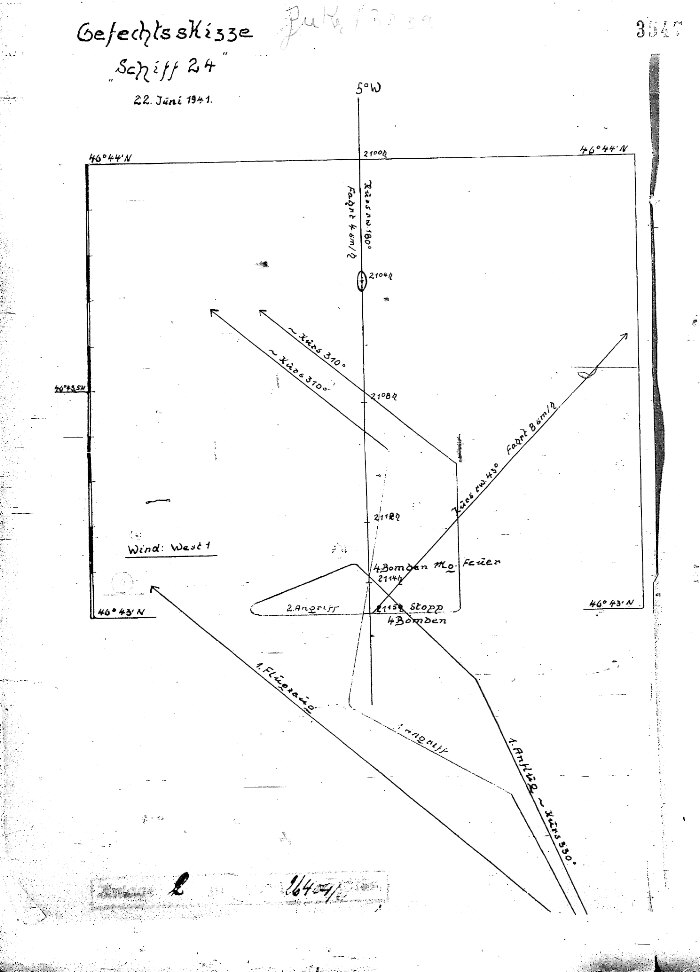

Ship’s position at 2100 hrs: Lat = 46° 44’ N

Long = 05° 00’ W

Wind: Westerly Force 1, Seastate: 0-1, Weather: scattered

cloud

Visibility: 18km, with the Sun in the West.

2105 hrs. The topdeck lookout reported “Aircraft off

the port bow”. The aircraft was an English machine

like a Lockheed Hudson, which was flying at about 400m

high on a course of roughly 310 degrees, 2000 meters

(estimated) past us in front. As was usual on the

appearance of a hostile aircraft the hatches were closed

and access onto the maindeck was forbidden. Two marines

acted as lookouts whilst working on the fishing nets.

2110 hrs While that aircraft was passing behind us to

starboard, another 2 aircraft were sighted flying side by

side ahead of us at a height of 50 to 60 meters. They

were of a similar type, and were flying towards the ship.

At that stage of the alert nothing was changed from what

I had decided on the 11 June with regard to provoking

low-flying aircraft. (See Ship’s Diary pages 36/37).

At a distance of about 1,000 meters the right hand

aircraft turned to port. I assumed that it would fly past

in front of us like the first one.

2114 hrs The third aircraft flew past close behind the

stern.

2115 hrs After the second aircraft that was apparently

flying on past in front of us had crossed our bows at

about 800 meters ahead, it turned to starboard and flew

towards the ship from a few degrees off the starboard bow

at low level. Since this kind of occurrence had already

happened on previous occasions, I maintained my original

course and speed, specifically to emphasise that my

Spanish disguise was genuine. About 50 meters in front of

the ship four Bombs were released, estimated at between

50 and 100kg in size. The bombs on these aircraft were

not hung externally but were carried in an internal

bomb-bay under the fuselage with 6 to 8 racks (like a

Sunderland or a Bristol Blenheim). One of these bombs

ripped through the aft mast at the height of the derrick

and exploded there. The other three landed 20 meters

behind the ship. On this occasion two explosions were

observed, at the impact and about 5 to 8 seconds

afterwards. It is probable that perhaps two bombs had

impact fuses and the other two had a time delay fuse in

order to be effective against submarines. Putting the

rudder hard to port and an increase in speed had no real

effect because of the short time between release and

impact (3-4 seconds) and the late stage at which the

order was given. On seeing the bombs being released I

ordered the air raid warning alarm but because of a

failure in the alarm system there was a delay before it

went out. As a result of that, the second electric motor

which is needed to operate the lifting mechanism for the

C/30 machine guns was not engaged straight away. Then,

because communication could not be established with the

engine room either by telephone or voicepipe and the

revolution counter indicated ‘stopped’, I

assumed that the attack had caused considerable damage to

the engine or to the personel on duty, so I ordered the

C/30 Machine guns to be deployed by hand and I sent a

runner to the engine room to report on the cause of the

engine failure.

2117 hrs Meanwhile, the aircraft that had flown past the

stern now made a low-level attack from the starboard

beam. Four equally spaced bombs missed their target and

exploded in the way that has previously been described,

about 50 meters beyond the port beam. No further attack

was made. Both aircraft flew off on a course of

approximately 310 degrees and were very quickly out of

sight. One aircraft got rid of its remaining bombs by

jettisoning them in the sea about 1,500 meters away,

without any target.

After the second attack the Engineer on Watch, Ob. Gfr.

Somerfeld (who was injured) came on to the upperdeck and

reported to me that he had stopped the engine since the

steam turbine had no oil as a result of damage to the

turbine oil pressure tank. In addition, a small fire had

broken out and filled the room with smoke but he had

checked that it had not spread. Straight after the first

attack Masch Mt Lehmann had hurried into the engineroom,

extinguished the fire and established that the engine was

capable of giving 9 knots. Since we could no longer

complete our mission, I took the decision to head

straight for Lorient. Clearing up the damage and work on

the camouflage began at once. And so, in the guise of a

normal Patrol Boat, I arrived in Lorient at 0730 on the

23rd June.

The conduct of the crew was exemplarary throughout.

DAMAGE

To Personnel: L.M. Obermaschinist d.R. Winzenburger, who

was positioned beneath the aft superstructure, died 1 ½

hours later.

Aft Lookout: Matr. Gfr. Krings, was killed instantly.

On watch in the Engine room: Masch. Gfr. Günter died ¼

hour later.

To Equipment:

As a result of the loss of the turbine the engine was

only good for up to 9 knots, and even that for a limited

time only.

The ship’s radio suffered from interference and poor

transmission for ½ an hour, since the aerial had been

completely destroyed.

The electrical system for firing the torpedoes was out of

action, and the air pipes for the aft tubes were split in

very many places.

The bearings for the 88mm gun were destroyed.

Two standby aerials were rigged up (3.5 meters for

transmission, 1.5 meters for reception) and 3 signals

were sent (see annexes 2-4). The battle damage report was

not acknowleged. I sent the other two signals in the hope

that Long Wave would not be swamped by static but

reception of any kind was unreliable - that’s why

signals number 19 and 20 were not received clearly. So I

sent a new request by Short Signal which is shown as

number 21 giving my intention to put in to Lorient, and

this was retransmitted satisfactorily.

As a result of this incident I asked (also by signal) for

a suitable berth to be made ready at Lorient if possible.

In addition, it was necessary to ask for medical help

(either a Ship’s Medic or a Doctor).

COMMENTS

I have two possible explanations for this attack:

1.) That, on 11 June, the English pilot took photographs

and our disguise was recognised. Under high quality

enlargement the fake was revealed, and the reason could

only be a Q-ship.

2.) On the same basis, the attacks on French fishing

boats can be explained: because of the lack of success in

hunting U-boats in the Bay of Biscay, the English suspect

that fishing boats are helping protect the submarines,

and want to destroy those that are fishing in the areas

which are declared to be inside the German blockade.

I suspect that the second case is the more probable. This

is suggested by the fact that if the ship had been chosen

as a specific target for bombing there would most likely

have been many more air attacks several days earlier in

order to guarantee success.

As a result of this attack a Q-ship was partially

destroyed and the existence of its guns was revealed.

Furthermore it must be noted that the crew would have

been spotted coming out of their quarters to get the

Anti-aircraft guns ready for action inbetween the first

and second attack, and so any continued deception by

having covers over the fish hatches has become useless.

Whether any of these points is true will become apparent

as a result of the future behaviour of English pilots

towards Schiff 13.

The attack shows once again the element of luck that

hangs over ships under such circumstances. There is no

way of telling whether the arrival of the aircraft was

intentional or merely happened by chance, so this raises

two questions, which must be clarified unequivocably:

1.) Should low flying aircraft be shot at ? (There is

about 40 seconds warning) The risk here is that because

of the lack of certainty of shooting down one aircraft,

let alone several, it would thereby further jeopardise

the current task and compromise the disguise for future

missions.

2.) After one low level attack should the camouflage be

maintained during future attacks?

Such questions are for a higher authority to consider,

but must be thoroughly discussed for application in sea

areas which are frequently patrolled by the enemy air

force.

This encounter with English pilots helps make it clear

that, whilst the second scenario did not happen in my own

case, the disguise should only be shed in the most

extreme circumstances and that is made obvious in the

enclosed War Diary.

So in summary the most likely sequence of events is

that the first aircraft to fly on past Schiff 24 is P/O

Williams who has turned North earlier than the other 2

Blenheims and does not attack. Five Minutes later

Charles' Blenheim jinks left then right to makes a

first-pass head-on attack from the South, with one bomb

exploding above deck level as it hit the aft mast

(possible interpreted as having 'bounced off the deck')

and thus showering the Blenheim with fragments.

Meanwhile, Eric Hewson flies past the stern of the ship -

perhaps to identify it, or perhaps because he was not

well placed to release his bombs - and then turns through

a wide circle to re-attack from the West. By that time,

well stirred up by Charles' bombs and forewarned by

Eric's manoeuvering, the ship's guns are now unstowed and

Eric is hit during his pass. Both Blenheims are seen to

fly out of sight to the Northwest, with Schiff 24 unaware

that they have dealt Eric's aircraft a fatal blow (and

hence why he is seen to jettison objects). Eric's own

account of the action reveals that they flew on for a

further 15 minutes before the aircraft broke in half and

crashed into the sea form a heigh of 10'. Link to the

'Hewson' page for a more detsailed account of his

adventure.

Note: All Coastal Command records give

ship's position as Grid DPCT 5254 = 4652N 0506W (which is

very close to Schiff 24's own record). One can probably

assume the Ship's log was more exact than that recorded

by the aircraft, which may have been taken a few minutes

after the attack.

TOP

|